This is a novel about two women – Melissa and Catarina.

Catarina is born to a well-known political family in Brazil. Melissa, a South London native, is brought up by her mum and a crew of rebellious grandmothers. In 2016, they meet for the first time.

Their story takes us across continents and generations. In it we see sisterhood and queerness, and, perhaps, glimpse a better way to live.

Forced enjoyment

This was the second book I had to read for class after Clarice Lispector’s Near to the Wild Heart. In fact, I chose this one due to its queer tag on Goodreads and hoped I would therefore find a spark of interest in it to draw me through the almost 500 pages. In the end, I was worried for no reason. I quite quickly enjoyed this novel’s exceptional style and grew close to the two main characters. Catarina and Melissa seem quite contrasting at first but discover not only mutual feelings but also a common heritage and history. Their friendship/potential romance drew me through the pages but was not the only thing this book had to offer.

A telling style

The author expressed in interviews that she chose her particular style for reasons of estrangement. As this story is most basically about a diaspora experience, she wanted to make her readers away of the irregularities and oddities involved in such a radical change of life. Her lack of punctuation and quotation marks emphasize her often lyrical style that contrastingly paces the reading compared to prosaic block paragraphs. More than that, the author uses whole chunks of texts in Portuguese although she wrote most of the book in English. Language thus becomes a signifier of rootedness that connects the characters to their origin but also to each other. Language further emphasizes the character development of both protagonists and their affiliation with cultures.

More than one story

There are eight big parts in this novel, excluding the pro- and epilogue. The individual storylines take for once place in London of the late 90s till the 2010s. Others are set in Brazil from the 60s to the 2010s. They are nonetheless not told chronologically but gift us with backstories of the protagonists’ childhood, alternating their present encounters. Moreover, the seventh chapters tells the story of Catarina’s aunt and her acquaintance. These two revolutionaries are on the run by 1970. Not solely with them, this novel is highly political and refers to several shocking events. Catarina and Melissa’s story is about activism, about living under a corrupt government, and about making one’s voice heard. It is also a story about love and resilience and friendship and heritage in the most special layout I have experienced for a long time.

In conclusion,

I was forced to read this book and am certainly thankful for it. Catarina and Melissa’s as much as their ancestors’ stories moved and mobilized me. The book surely expects some political knowledge and makes the readers aware of their lack of it as much as of the strange- and commonness of the characters’ experiences.

The author:

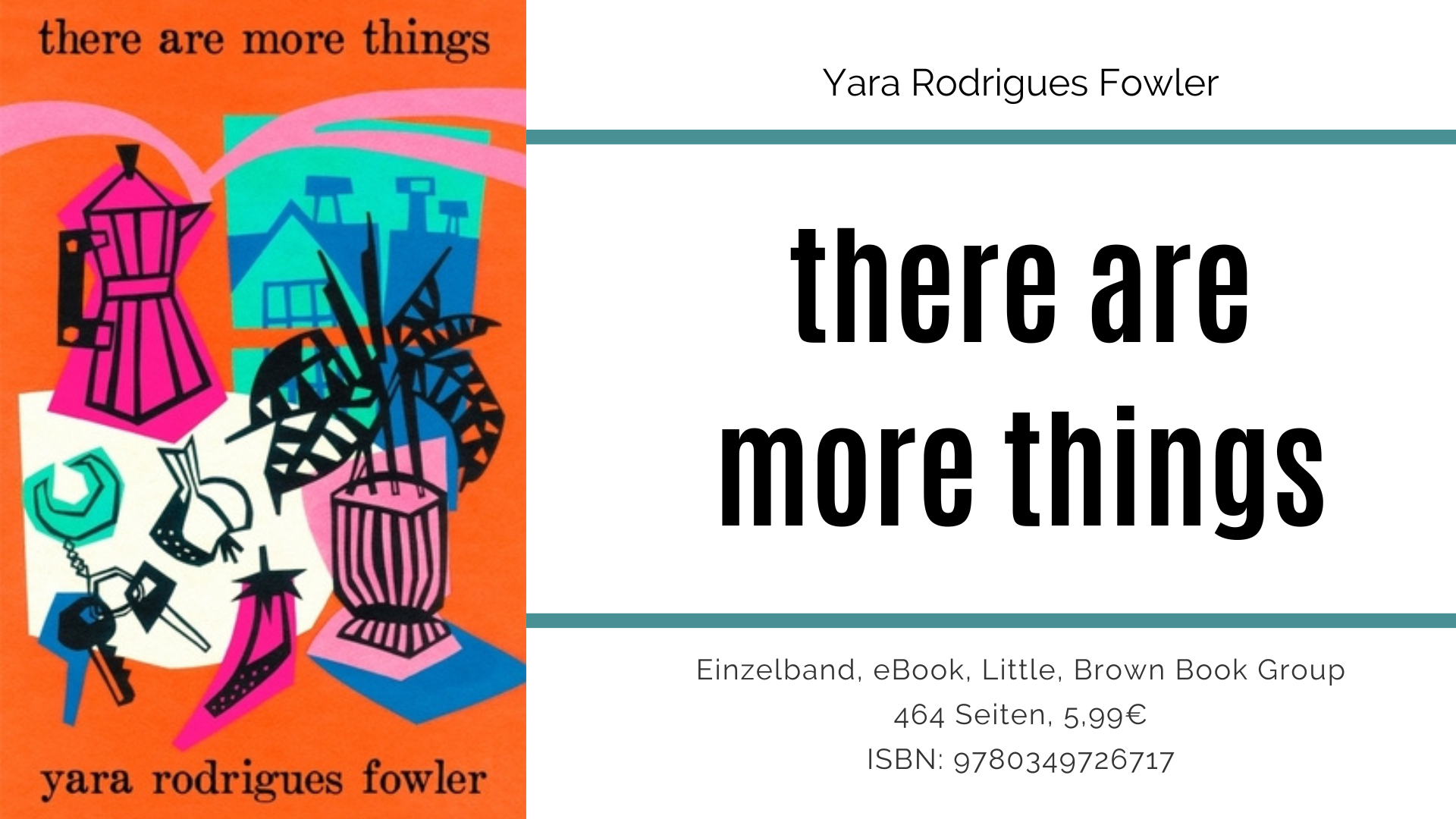

Yara Rodrigues Fowler, 29, is a Brazilian-British novelist and activist from London. In 2019 she was shortlisted for the Sunday Times young writer of the year award for her debut, Stubborn Archivist, cited as “a formally inventive novel of growing up between cultures”. That same year, the Financial Times named her one of “the planet’s 30 most exciting young people” after she was credited with boosting youth turnout in the 2017 general election, when she co-created a bot that encouraged Tinder users to register to vote. Fowler’s new novel, there are more things, turns on the political awakening of Melissa and Catarina, two London flatmates with roots in Brazil. Source